A Long Overdue Eulogy: Anthony Bourdain and The End of Empathy

Last month, at the recommendation of a friend, I listened to my first ever Invisibilia podcast. Invisibilia — NPR’s breakout podcast — explores the invisible forces that shape human behavior — things like ideas, beliefs, assumptions and emotions, and is co-hosted by two of NPR's award-winning journalists, Alix Spiegel and Hanna Rosin. It was launched with the hypothesis that we can always see a facet of ourselves in each other if only we would share our personal narrative. The episode I landed on was “The End of Empathy”, a narrative questioning whether or not we should realize empathy via the path of storytelling.

Equal parts thriller and self-help (if such a pairing is even possible), this particular episode takes a sharp left from those of past seasons. As the episode unfolds we are introduced to Jack Peterson, a reformed “incel” or involuntary celibate — a subversive online subculture of men (current estimates have the number in the tens of thousands) who define themselves as unable to relate to or sexually connect with women despite desiring to. This episode, in particular, was unusual as the first part of the episode is essentially part of a job interview by a now producer of the show, Lina Misitzis. Misitzis is tasked with taking an existing Invisibilia story and creating one of her own. From her tone and description, I am guessing she is a young 20-something woman. A Gen Z’er. A member of what many see as an angry, self-righteous and somewhat bullying generation. "A generation without empathy," some say.

Though “The End of Empathy” is part podcast, part job interview, it brilliantly results in a tale analyzed through the lens of two generationally disparate individuals and their attempt to reconcile these differences…at least on the topic of empathy. The first take is done by Rosin who approaches the story from a place of empathy and understanding — the “why and how” behind Peterson’s view of women. Her desire, I am guessing, is to empathically balance the danger of his particular views (and behaviors) with the underlying story of how he arrived there.

In contrast, the second pass by Misitzis (the job seeker) doesn’t extend this same level of empathy to Peterson. In fact, by the end of her story, you realize she doesn’t extend it at all. What she seemingly concludes is that Peterson is not deserving of her empathy. That to extend him this courtesy denies his victim (a former girlfriend) the empathy she is far more entitled to.

By giving us this multi-lensed view into Jack Peterson’s story, “The End of Empathy” exposes us to the well-discussed gap in generational culture (e.g. the difference in our approach to empathy). Studies even show that millennials are somewhere in the neighborhood of 40 percent less empathic than the previous generation. Like with many things these days, millennials take a tribal approach to empathy, seemingly extending it only to those who make up their tribe; their friend group; their community. So, as Misitzis sees it, why would a woman (in particular, her) empathize with someone like Peterson?

The clear disconnect between Rosin and Misitzis highlights a growing divide between what younger and older generations value and the speed with which societal and cultural norms shift. In this case, the clear gap between how and when empathy should be meted out.

After listening to the episode a second time, I actually wondered whether this story was actually a critical elucidation on the Gen Z generation wrapped in incredible storytelling. Or was it a challenge to a long-held assumption — an assumption that people are inherently capable of empathy? Or whether there is even value in trying to see things from another person’s perspective?

It was at this point that I thought about the life of one of my heroes, Anthony Bourdain.

Although I did not realize it until his suicide in 2018, Anthony Bourdain played a powerful role in the formation of my outlook on people and culture. He also played a strong role in my later “sojournistic” pursuits. Look past his irreverent mannerisms, rough exterior and overzealous alcohol consumption, Bourdain was one of the most complex and byzantine of men. For those unfamiliar with this larger than life individual, I wish I had the adequate words to fully describe him. So instead, I will let Will Fulton, author of Anthony Bourdain's 23 Essential Quotes on Food, Traveling, and Life express what I cannot:

[Anthony Bourdain] spoke his mind. He had balls and the brain to match. He had convictions. He held on to his worldview with a rigidity that was both refreshing and borderline revolutionary for someone in his position: he was a chef who spoke the hard, often brutal truths about his industry, a travel guide who cut through the sanitized, force-fed [b.s.], a media icon who wasn't afraid to be criticized, ostracized, or demonized if it meant standing by his own words.

But for all his steadfast positions on everything from scrambled eggs to Guy Fieri, he held one belief, unwaveringly: He wanted to make the world a more inclusive place. He implored people — Americans, specifically — to give their comfort zones a well-deserved [night off]. He embraced and celebrated the humanity present in every culture, in every region, in every hole-in-the-wall noodle shop in Singapore or Michelin starred restaurant in Pairs, equally. He poured enough life into his 61 years on this earth to inspire a generation to travel with passion. To eat with an appetite. To drink with a stranger. To love, to swear, to sweat, and above all, connect with our fellow human beings.”

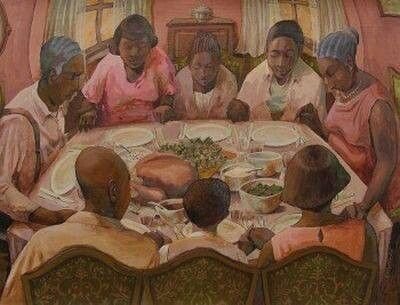

I discovered Bourdain almost a decade ago through his show No Reservations, a food and travel show that originally aired on the Travel Channel in the US. From 2005 to 2012, Bourdain invited us to join him on a journey. His beckoning hand asked us to walk with him on a bold and sensual journey into parts unknown (the title of what would become his final show on the CNN channel). Every week he introduced us to the outlandish and peculiar — the extraordinary aspects of cultures and traditions from across the globe. Within fewer than 60 minutes, he was able to turn faraway strangers into personal friends, weaving their tales alongside the unifying power of food. Every week millions of us tuned in to join him. More often than not, by the end of each episode we were left with the feeling that we had stepped into a different reality, perhaps with the recognition that no matter how strange the food or how different the culture, the people whose lives we so fleetingly entered into were really not much different than our own.

For some of his audience, Parts Unknown was their journey of a lifetime as few of us ever get to experience the kind of international travel that Bourdain did. Those of us who have traveled the world eventually recognize just how incredibly sacred the opportunity is to travel to far-away cultures and communities in an immersive manner leave those places knowing that a part of us will always remain there. Yet, somehow, we always return feeling more whole than when we left.

Bourdain, who is well respected in the culinary world as a chef and author, ended Parts Unknown with one of his trademark postscripts - a moving exhortation that is equal parts wisdom and counsel:

It’s been a wild ride.

A lot of miles. A road sometimes smooth, sometimes hard and ugly.

And I guess I could tell you that if you look hard enough, that next door is just as interesting as the other side of the world.

But, that’s not exactly true.

If I do have any advice for anybody, any final thought, if I’m an advocate for anything, it’s to move.

As far as you can, as much as you can.

Across the ocean, or simply across the river.

The extent to which you can walk in somebody else’s shoes — or at least eat their food — it’s a plus for everybody.

Of course, Bourdain wasn’t only talking about travel. Yes, the ability to truly travel — not as a traditional tourist but as a voyager – changes you if you let it. It slowly decreases the fissure of unfamiliarity and minimizes the difference in miles traveled. What it ultimately does is birth an empathic response typically saved for our family and friends back at home. Bourdain was also talking about connection — connection to the stranger across town or across the ocean. His greatest desire was to understand what makes people different; what makes them tick; the things they care about and why.

If nothing else Bourdain made us think. He challenged us to seek out our similarities rather than our differences, even question why we would think we are all that different in the first place. And though he rarely shared his own opinions, ideology or even theology, one thing was clear: Anthony Bourdain loved people. And in the process of loving people, he silently held up a mirror to the superficiality and polarity of political and social norms. Anthony Bourdain taught us not to ignore our differences, but rather that our differences can be beautiful, inviting, and connecting. In his journeys to parts unknown, he taught us that not only are our differences important but that they are often worthy of celebrating.

This isn’t to say that Bourdain was blind to the sources of pain and hardship experienced by the people he met. Nor did he overlook our political and ideological differences. But he somehow found this magical ability to call out wrong and evil in an empathic way. He was able to highlight the evil in the world with both honesty and humility. He never fancied himself a judgmental insider, but rather considered only “the what” of each situation as a sacred opportunity to expose wrongs and right injustice. He left “the how” to the rest of us.

In a 2017 Forbes interview, Brene Brown — one of today’s foremost experts on vulnerability and courage — was asked an important question, one we are all likely asking ourselves today:

Why do we currently have a crisis of disconnection in our society and why do you believe a sense of true belonging is the solution?

Her response is one that should encourage us all, as it is clear she believes that the state of human connection is not irreparably broken. That it is not only possible but probable that the social web upon which community and connection are founded can be stronger than ever before:

We’re in a spiritual crisis, the key to building a true belonging practice is maintaining our belief in inextricable human connection. That connection — the spirit that flows between us and every other human in the world — is not something that can be broken. However, our belief in that connection is constantly tested and repeatedly severed. When our belief that there’s something greater than us, something rooted in love and compassion, breaks, we are more likely to retreat to our bunkers, to hate from afar… and to dehumanize others.

In this quote, Brown makes it clear that human connection — the foundation for empathy — is as much action as it is emotion. Our ability to empathize is directly tied to our ability to emotionally connect with other people. In a 2012 Psychology Today article titled “Empathy: The Ability that Makes us Truly Human”, author Dr. Steve Taylor says the following: “…empathy is…a cognitive ability, along the same lines as the ability to imagine future scenarios or to solve problems based on previous experience. But in my view, empathy is more than this. It’s the ability to make…an emotional connection with another person…When we experience real empathy or compassion, in a sense our identity actually merges with [theirs]. Your ‘self-boundary' melts away; the separateness between you and the other person fades.”

Taylor goes on to say: “Our strongly developed sense of individuality — being a personal self, or ego — can make it difficult for us to experience this state of connection. The ego walls us off from other people, particularly those belonging to groups unlike our own. It encloses us in a narrow world of our own thoughts and desires, making us so self-absorbed that it's difficult for us to experience the world from another person's perspective. Other people become truly “other” to us. And this makes it possible for us to inflict suffering on them, simply because we can't sense the pain we're causing them. We can't feel with them enough to sense their suffering.”

The Bible has its own version of the more empathic way:

He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God? Micah 6:8

Put on then, as God's chosen ones, holy and beloved, compassionate hearts, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience, bearing with one another and, if one has a complaint against another, forgiving each other; as the Lord has forgiven you, so you also must forgive. And above all these, put on love which binds everything together in perfect harmony. Colossians 3:12-14

Like Jesus (oh, how Bordain would have marveled at that comparison), Anthony Bourdain wasn’t afraid of the “sojournastic” life — the ability to live as an alien in an unfamiliar land. He travelled not as a tourist but as a human investigator seeking to understand the uninvestigated. At a time when civility, compassion, and empathy, much less the desire to embrace and understand the unfamiliar, feels so tenuous, his absence from our screens and from our world leaves behind an undeniable void.

We will never know if Anthony Bourdain knew going in the impact his show would have on him personally. We can’t assume he knew that the simple practice of experiencing foreign foods and cultures would change him, would make him softer, more caring, more empathic. We will also never know how close he felt to those whom he would eventually leave behind after filming ended. But I think I can guess.

Bourdain once said, “I don’t have to agree with you to like you or respect you.” Never has a simpler or more profound sentence been spoken. Yet, what on the surface seems so easy is actually one of our most challenging calls to action. Our inability to embrace this commission is at the center of the division and distrust present in our culture, our politics, and our global community today. It is foundational to increasing suicide rates, hate crimes, social disconnection, and political dysfunction. Sadly, we have never needed Bourdain’s voice more.

At the top of “The End of Empathy”, co-host Alix Spiegel shares a somewhat contrarian description of Invisibilia to that of NPR’s. While NPR categorizes Invisibilia under “Science and Medicine” (a neuroscientific examination of the brain and its influence on thought and behavior), Spiegel introduces a new perspective: that “the Invisibilia way is the empathic way.”

“Empathic? How can a science and medicine podcast about the brain be empathic?”, I thought. “Empathy is the thing one does from a place of emotion. It is something that emanates from the heart, not the head”, I assumed.

But listening to “The End of Empathy” upended my way of thinking about the empathic way. For perhaps the empathic way is actually medicine, and maybe it is about the head and not the heart. Conceivably empathy just might be a practice that begins in the brain, and when we practice it often enough, it begins to touch our heart.

This might also mean that empathy isn’t dead at all, as the Invisibilia hosts surmised partway during the show. Perhaps it has just gone dormant or shapeshifted into any manner of self-help invocations or millennial-esque psycho jargon. Or maybe, just maybe, we’ve come to favor instead its application to those whom we deem worthy — the trusted members of our natural or adopted tribes.

I believe a broken heart may have contributed to Bourdain’s suicide. On his many journeys, he somehow managed to fill his heart with every human life he entered into. And before he knew it, it was filled beyond capacity. It broke from his inability to deny anyone else entrance. Embracing both the joy and suffering of the human experience, Bourdain simply sat with it. He didn’t ask it to change and he didn’t try to actively change it. He simply asked to see it. And he ate some pretty good food along the way too.

At a time when we might question our ability to find our way back to the empathic way – as individuals, as a nation, and as a global community, I pray that we might honor Anthony Bourdain once more, and the many others like him who know the empathic way all too well. May we honor them by jumping into the pain-filled, messy world which we inhabit; that we might give some respite to those like Bourdain whose hearts are filled to capacity. We cannot risk losing any more of them.

And so, I beg you to find your own way of empathy. Lean into the differences that so easily divide. Embrace the messiness that only humans can create. And moreover, learn to sit with the suffering of others. I believe that the greatest gift we can give others is the gift of empathy. It is also the greatest gift we can give ourselves. Because when you sit and just listen, attempting to understand not just the how, but the why of another person’s story, the hard path towards empathy becomes much, much easier.